Have you joined the cult of Ottolenghi?

Maybe you’ve joined just one sect—the Jerusalem sect? The Simple sect, the Plenty sect, the Sweet sect?

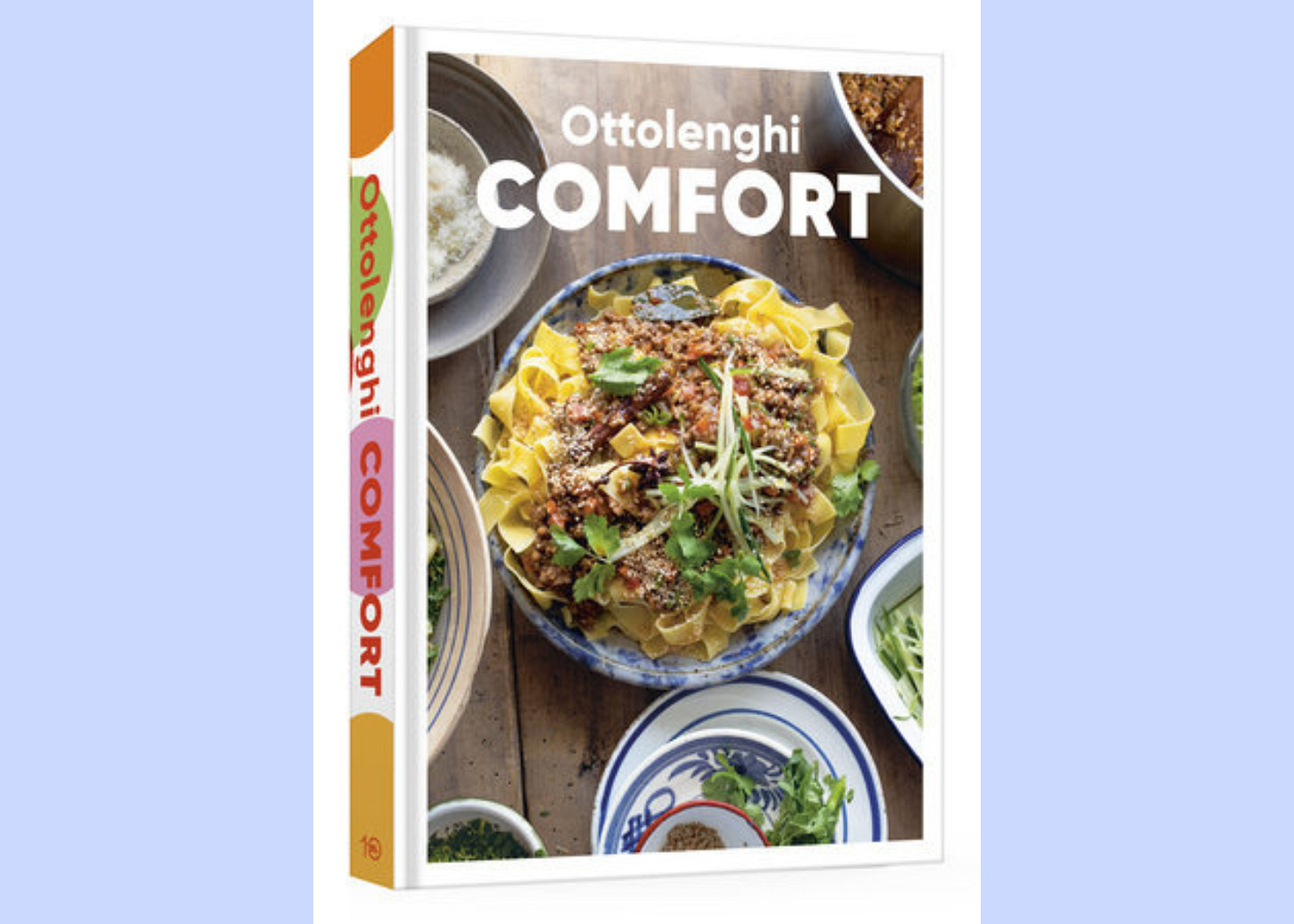

But if you’re all in, then the newest sect may bring you comfort and joy.

Comfort is the eleventh Ottolenghi/Ottolenghi Test Kitchen book, alongside his Guardian and New York Times columns and the restaurants that started it all (now up to 10 locations), plus streams of public appearances. To say the man is literally everywhere feels like a bare misuse of “literally.” Likewise his favorite ingredients: Supermarkets now regularly stock items he popularized that once were obscure and hard to source, such as sumac, preserved lemon, harissa, and za’atar—often combined in nonobvious and bordering-on-weird ways.

Ottolenghi’s early books prompted comments like this from Geraldine DeRuiter: “Yotam Ottolenghi’s recipes contain forty ingredients and you have to start making them six months ahead because you have to grow the herbs from scratch or leave your spices out until a full moon and then you have to lure virgins to dance around them until they are all so exhausted that they collapse and that is a lot to do for a risotto.”

A gentler route into the cult came with the publication of Simple, which offered recipes with no more than 10 ingredients, making them, by Ottolenghi standards, simple, often doable for a weeknight supper, and often falling into the “comfort” camp.

Now Ottolenghi and his team of recipe developers offer Comfort, with recipes to evoke memories and warm feelings. What that means depends on the authors’ cultural touchpoints, so you might find meatloaf here, but a shawarma meatloaf, or stretchy aligot potatoes with leeks and thyme and garlic instead of plain mashed potatoes. The flavor repertoire branches out from the Ottolenghi classics by encompassing the comfort foods of his co-authors—influenced by China, Malaysia, Australia, Scotland, and London—alongside Ottolenghi’s German and Italian Jewish heritage and his Jerusalem upbringing.

Comfort, of course, doesn’t have to mean quick—think cinnamon buns or multilayered lasagna. But somehow a glance at Ottolenghi recipes, even with lots of less-common ingredients, always suggests the prep will be quicker than the reality. The final products may taste incredible, fresh, and different, but first there’s the finding, chopping, processing, and cooking the ingredients that invariably takes longer than expected, even for accomplished cooks.

And sometimes, despite the strong flavors, Ottolenghi recipes often feel too much the same. For all the ingredients in some of them, the flavors can fall a little flat—maybe because nothing stands out, sometimes because a dish needs acid to brighten it. The varied flavors his co-authors contribute help with the sameness, but there’s still plenty of the classic Ottolenghi hits like preserved lemon, black garlic, Aleppo chile, and curry leaves to go around here.

The book opens with some accessible, familiar breakfast options with a twist: Dutch baby with roasted tomatoes, a sambal-flavored shakshuka, leek, tomato, and turmeric frittata, and an omelet with eggplant (featuring one of the least appealing food photos you’ll see in a while), and crepes. For a flavorful spin on Nutella to fill the crepes, Comfort offers a chocolate spread made with sesame and hazelnut praline. Is the praline worth the effort? Debatable—definitely delicious, but also time-consuming: Toast seeds and nuts in the oven, stir them into just-made caramel, let harden, bash with a rolling pin, grind for 10 minutes in a processor, then add oil and vanilla seeds. Only then do you start to melt chocolate to finish the recipe. This could have benefitted from a touch of salt, and no matter how long the processing, it can’t escape a slight grittiness—not unpleasant, but not silky like Nutella.

In contrast, making the batter for thousand-hole pancakes takes mere minutes, but the flavor payoff isn’t there. Inspired by Moroccan pancakes, these start with a mix of semolina and bread flours, a dash of sugar and salt, yeast, and water, blended til smooth before an hourlong rest. Cooked one at a time in a small nonstick pan, the 12 thin, chewy pancakes, vaguely reminiscent of injera, take around 30 minutes to cook. After cooling a bit, they get spread with a mixture of butter, honey, salt, orange blossom water, and pecans. The butter or another topping is crucial for the nearly flavorless pancakes; possibly following the option to leave the batter overnight in the fridge would develop more flavor and tang. (A quibble in the way these recipes are written: The ingredient list for the honey butter calls for a half-teaspoon of salt, but for the pancakes just says “salt.” The instructions then say to put all the ingredients in a blender plus a half-teaspoon of salt. It’s minor, but, as proven in recipe testing, the inconsistency also makes it more likely a cook will overlook the salt—and this recipe needs every bit of seasoning it can get.)

Far more successful was the roasted eggplant, red pepper, and tomato soup. Again, cooks can’t speed through, with oven-roasting, then peeling those vegetables while onions, spices, and tomato paste get sauteed. But the soup’s deep flavor—even without its fried almond topping—will make cooks wish they’d prepped a double batch, to keep a stash in the freezer.

For another comfort food with a twist, Ottolenghi replaces tahini in hummus with fennel. Tested with canned chickpeas (given the challenge of finding the required “jars of good-quality chickpeas”), the anise seemed surprisingly muted here; the suggestion to use Pernod instead of vermouth could have boosted a mild fennel bulb. Topped with a mixture of roasted bell pepper and cherry tomatoes spiked with garlic and olives, though, this made a pita-worthy alternative to standard hummus.

Rice fritters spiked with feta and mozzarella, with scallions, Greek yogurt, frozen peans, and nigella seeds adding flavor came together quickly, though the 1:1 ratio of rice to water left the rice bordering on crunchy. That made it tricky to hand-form balls and press them into patties that held together; better and quicker was to put a scoop straight from the mixing bowl into the skillet, then flatten it. Served with a quick sweet chile sauce, these crisp cakes hit the comfort mark.

Sometimes the odd choice to make the ingredients list not match the order of preparation feels annoying when trying to move efficiently through a recipe; the first step in a dish of ramen noodles with mushrooms called for making the sauce first, though the sauce ingredients are listed after the mushrooms, noodles, and garnish. And this supposedly 15-minute recipe takes the cook all the way through making the green onion sauce, then cooking the mushrooms for 15 minutes, before telling the cook to put on a pot of water to boil for the ramen. The first step in any noodle recipe should always be that pot of water, as most cooks know. (The dish was fine, though flavor-wise a little underwhelming.)

Rigatoni with a tomato-less ragu had the interesting addition of a pureed potato paste (again listed midway down the ingredients list, but prepared in the first step), flavored with garlic, sage, rosemary, and anchovies. Added, with chicken stock, to a sauteed mixture of wild mushrooms and ground beef and left to simmer for 90 minutes, the ragu wanted a touch of acid to lift the flavors beyond what a dusting a lemon zest, parsley, and parmesan could provide as a garnish.

Comfort offers a host of vegetarian recipes, making this a great book for a cook putting together a spread for both meat-eaters and not. Think crisp cauliflower and butternut pakoras alongside shrimp fritters; vegan creamed spinach and artichokes; mushroom ragu; coconut rice with peanut sauce and cucumber relish, served with or without sambal spiced chicken and more sauce; green tea noodles with avocado and radish; caramelized onion orecchiette with hazelnuts and fried sage; zucchini and fennel lasagna for eight or sauce ragu lasagna for one; beef, black garlic, and Baharat pie; and leek, cheese, and za’atar rugelach. The book closes with some savory breads and a few sweets, such as a marble cake, cheesecake, vegan Texas sheet cake, and chocolate mousse with orange caramel.

As cults go, joining Ottolenghi’s can give you a sense of community, with rabid followers around the world, joy at successfully completing its required tasks, weariness in following its sometimes arduous tasks, and a push-pull on your wallet (specialty ingredients pull the money out, while often-cheaper vegetarian recipes push some back in). Give the Comfort cult a whirl—but walk back guilt-free if needed to Simple, or away altogether.

Quick takes:

Ottolenghi Comfort, by Yotam Ottolenghi, Helen Goh, Verena Lochmuller, and Tara Wigley. 318 pages. Published by Ten Speed Press, 2024.

Organization: Chapters organized by type of dish, such as “eggs, crepes, pancakes,” “fritters and other fried things,” “roasted chicken and other sheet pan dishes,” “dals, stews, curries,” and “pasta, polenta, potatoes.”

Ingredients measurement methods: A mix—olive oil may be listed as ¼ cup/60 mL, while cilantro is listed just as 2½ ounces/70 grams (no volume measurement given), and honey just as 2 tablespoons (no grams given, annoyingly for something sticky like this that has to be scraped out of the tablespoon).

Photos: Photo illustrates each recipe.

Index: Comprehensive.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org, which supports independent booksellers, and I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase on the title above.

The Spice of Life

Everything is better with Pepper

Comfort is walking with your best (ahem, only) dog friend.