Blended Enough: Bridging Cultures with Homestyle Chinese Food

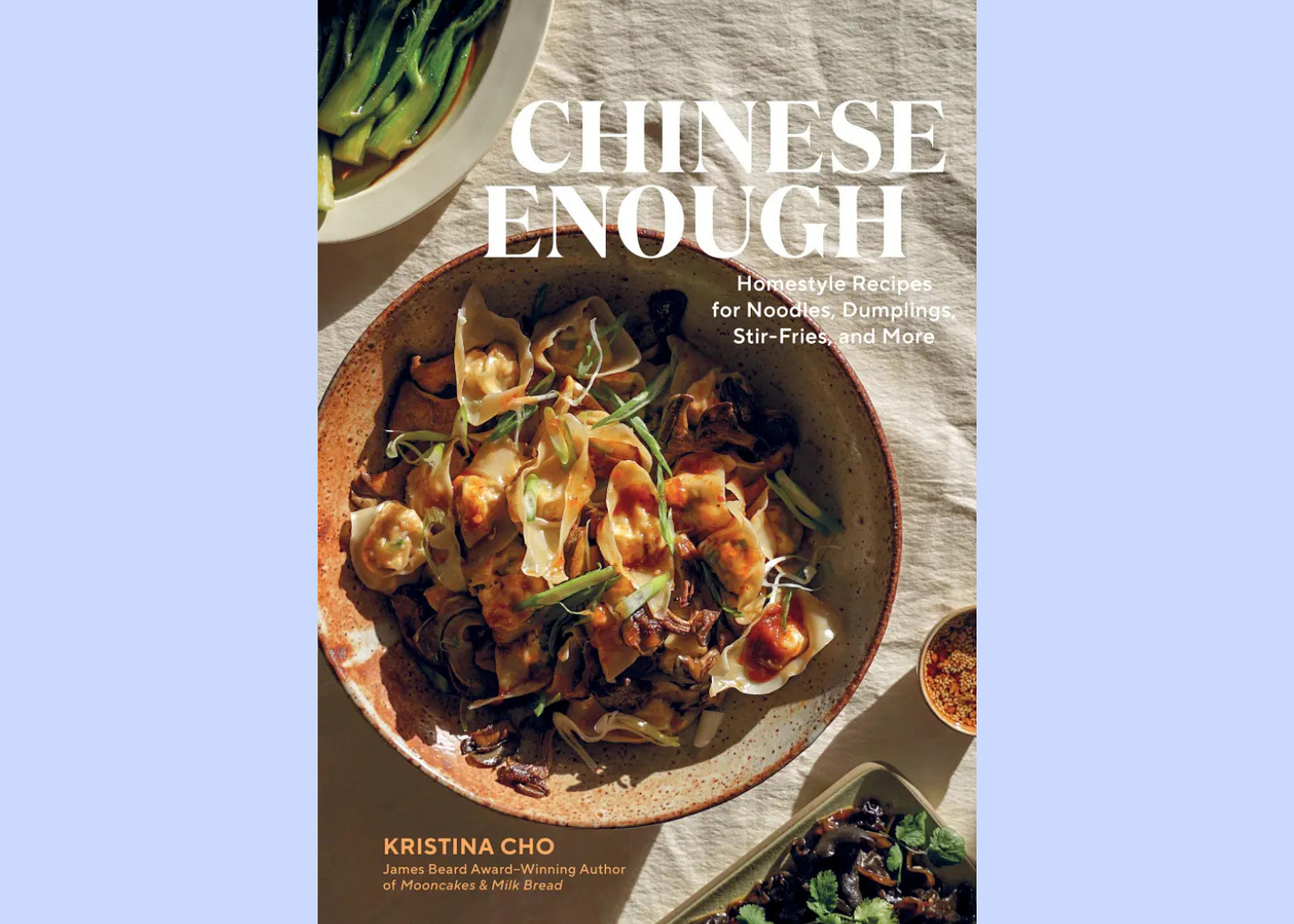

Chinese Enough: Homestyle Recipes for Noodles, Dumplings, Stir-Fries, and More

You are enough: Kristina Cho now knows it about herself, and with Chinese Enough, it’s a message she aims to spread.

Cho grew up in a Chinese family in Cleveland, but went to school with mostly white students, leaving her feeling not Chinese enough with her extended family—lacking fluency in Cantonese and dressing like an American—while not American enough at school. But over time, she shifted an ongoing love of cooking to include more Chinese foods, and career-shifted from architectural design to become a James Beard Award-winning food writer (for her first book, Mooncakes & Milk Bread). Alongside a move to San Francisco, her acceptance of all the facets of herself grew.

In Chinese Enough, Cho intersperses short essays about aspects of cooking and family life throughout the recipes, all coming at the “You are/I am enough” idea. While talking about straddling two cultures and feeling like never being enough in either isn’t new, the essays add weight and texture to her theme.

After including a helpful section on needed tools and knife cuts for her recipes, Cho turns to chapters organized by how she likes to serve a meal, such as recipes for cookouts, for preparing as a group (such as a strong section on dumplings and spring rolls), for banquets, or for dishes best served with rice. So the rice chapter includes orange pepper popcorn chicken, sticky maple tofu sticks, green steamed egg, and miso pork meatballs. Noodle recipes include creamy tomato udon, mushroom chow mein, peanut butter and cheung fun, and Spam and mac soup. Each chapter opens with a recipe list—helpful given this less-than-intuitive organization.

Recipes seem especially appealing to cooks with a multicultural heritage along the lines of Cho’s, seeing how she melds her Chinese, midwestern, and Californian influences, as well as to non-Chinese cooks open to the mix of comfort-food recipes such as “mom’s spaghetti,” which incorporates oyster sauce and ketchup into its ground beef topping, and less-familiar ingredients such as salted egg yolks, used in a batter for fried squash rings.

Red-braised lamb, tea-brined duck breast, wood ear mushroom salad, saucy sesame long beans, and steamed bitter melon stuffed with black bean and garlic pork have a more traditional feel. Other recipes incorporate more influences, such as a white and black bean dip mixing fermented black beans, garlic, and rice vinegar into a white bean puree; hot honey mayo shrimp; curried surimi salad; smashed ranch cucumbers; soy caramel apple cake; malty banana cream pie; and Cleveland-ish cassata cake.

These culture-bridging recipes still require many traditional ingredients; Cho includes a chapter on stocking the pantry, including some brands she prefers. The recommendations seem worth heeding; a recipe test of eggplant scented with a lime and basil sauce would have been better with a less overpoweringly funky fish sauce. She says her recommended brands include a little sweetness, which could have helped.

Typhoon deviled eggs top a sriracha-kissed yolk filling with typhoon breadcrumbs, a popular Hong Kong mixture sprinkled over seafood, Cho says, and Chinese pork floss. Tested minus the pork floss, these eggs were still a hit, with the crunchy mix of panko, scallion, garlic, and ginger offering powerful flavor and pleasing textural contrast to the smooth egg.

And flavorful miso pork meatballs come together quickly, with ground pork spiked with miso, ginger, and scallions. These made a light but flavorful simple entrée served over rice (without, she says, any sauce, though her suggestion of sriracha and Kewpie mayo is a good one for people who really want sauce), or a good addition to a multilayered rice bowl.

Small shrimp patties, despite looking like standard fish cakes in the photo, add a step of boiling the patties before frying, creating, Cho says, a cloudlike interior. These were only half-successful in a recipe test. The shrimp mixture, which includes baking powder, comes together quickly in a food processor, then gets portioned with a small cookie scoop into boiling water. That means each scoop goes into the water in a ball, not a flatter patty, dramatically puffing up and out in an explosion of shrimp paste. From there, it’s to be pan-fried until crisp, but the puffed exteriors were too irregular to make great contact with the hot oil for consistent crispness, though the interior was cloudlike as promised.

Whitefish Rangoon, though, was another hit, mixing smoked mackerel and cream cheese for a fried wonton filling. Reasonably quick to prep (especially with two cooks working together) and served with Cho’s pineapple sweet-and-sour sauce, these sucessfully blended cultures (her husband is Jewish) without feeling forced or gimmicky. The uncooked wontons also froze well, making it useful to prep a full batch or two to have some on hand for last-minute frying once you’ve started the work of filling and shaping these.

Cho closes with a dozen helpful menu suggestions, to serve two, four, six, or eight guests—a nice touch for the many good cooks who nevertheless may feel they are never enough when it comes to putting a menu together.

Quick takes:

Chinese Enough, by Kristina Cho. 367 pages. Published by Hachette Book Group, 2024.

Organization: Organized by how Cho likes to serve a meal.

Ingredients measurement methods: Ingredients are listed by both weight and volume, with Cho encouraging cooking by weight.

Photos: Photos accompany every recipe, and Cho sprinkles in useful photos illustrating techniques such as how to pleat dumplings or form spring rolls.

Index: Reasonably comprehensive.

Disclosure: I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org, which supports independent booksellers, and I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase on the title above.

The Spice of Life

Everything is better with Pepper

Don’t let anyone box you in; Pepper doesn’t, and she believes you, too, are enough.